Thomas Selby – additional information

The Selby name

It is very likely that Thomas Selby (and George) were linked to the Selbys of Ightham who owned Ightham Mote for a long time – but the link has not yet been established. Information on Thomas Selby and his immediate family can be found here. The early part of the family tree of the Selbys of Ightham can be found here.

Another tantalising Selby has also emerged. Dorothy Selby (1572-1641) married William Selby III, and she was a daughter of Charles Bonham of West Malling. The marriage was brokered by Walsingham, the Tudor spymaster. There is a bust of her in Ightham church which is said to have been carved by the Master Mason to the Crown, Edward Marshall, and as she was childless, several children feature on the memorial. Her claim to fame is that it is said that she exposed The Gunpowder Plot. Her love of needlework was her downfall, as she pricked her finger and died of blood poisoning.

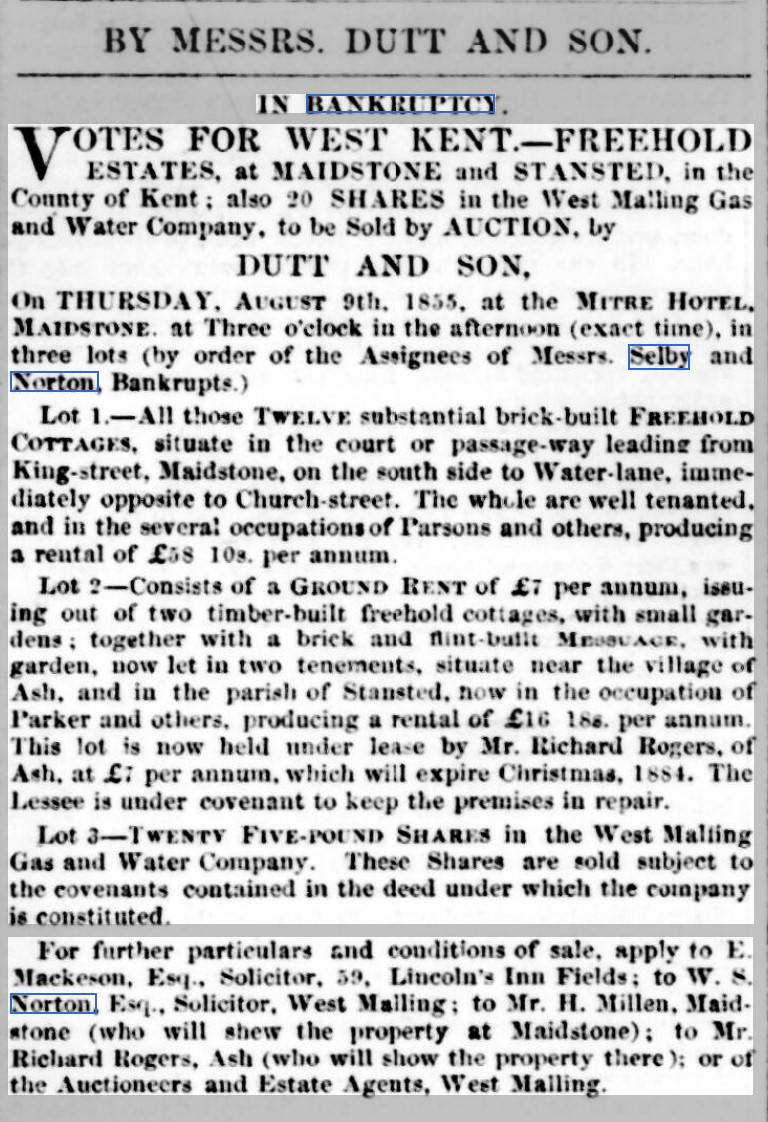

The bankruptcies

Thomas Selby, Silas Norton and George Selby dissolved their partnership on 25 March 1844. This was almost certainly caused by the enormous debts they had accumulated, and they all became bankrupt. They applied for their certificates (of discharge) late in 1855, George on his own account as he worked out of London, and Thomas and Silas jointly. The court hearings were reported in detail in the Maidstone Advertiser and Kentish Advertiser, Thomas and Silas on 6 November 1855 and George on 11 December 1855. The reports can be found in the British Newspaper Archive, but readers will need to set up an account.

In the judgement on Thomas and Silas given on 23 November, the judge allowed Silas his certificate (although with a one year suspension), but denied any certificate for Thomas. He was judged to have committed fraud and a breach of trust in dealings with George and a Mr Hodges, George’s business partner in a manufacturing venture. Thomas had a deficit of funds of over £34,000. This was after he had sold his private property. He went to appeal, but lost that as well. The appeal court judges said Thomas’s conduct was “a breach of every duty which he owed as a solicitor to his client, and amounted to a malversation of the most serious character.”

George was not so harshly punished as his brother. He was judged to have been an accessory after Thomas’s fraud, and was granted his certificate, but suspended for two years. In giving his judgement, Commissioner Evans said this was the “case of a man who had once filled a most respectable position, and had carried on business in London as a solicitor. Like many others, he was not satisfied to let well alone, but had resorted to a variety of speculations, had entered into various partnerships, and had carried on several schemes until he had left himself in the court in the melancholy position of owing debts and liabilities to the amount of nearly £200,000, and had not sufficient to pay his creditors a farthing in the pound.”

As well as being a solicitor, one of George’s “speculations” was in the manufacture of iron and brass tubes, with his client and partner Mr Hodges. There is a lot of information on them here, but refer to pages 65, 74, 76-80, 92, 93, 129-133. The author describes George as “a very clever but dishonest solicitor: a fraudster and an archetypal Dickensian villain. Hodges, his client since at least 1828, was possibly just one of many that [George] Selby had defrauded during his, seemingly, successful career as a lawyer and businessman.”

Ashford & Tenterden Canterbury, Herne Bay and Whitstable Dover, Deal & Sandwich Faversham, Isle of Sheppey and Sittingbourne Folkestone, Hythe & Romney Marsh Gravesend & Dartford Maidstone Margate, Broadstairs & Ramsgate Rochester, Chatham & Gillingham Sevenoaks Tonbridge and Malling Tunbridge Wells